Professional espionage is not a common item in a writer’s bio, but those who have it usually show a remarkable talent for building a sense of intrigue, genuine characters, and outstanding plot twists. After successfully pivoting from one calling to the other, many of them helped establish spy fiction as a genre rich in thrilling action, exotic settings, political affairs, and courageous secret agents.

For others in this group, however, such experiences were never a defining aspect of their literary oeuvre. Still, indirect influences could be traced in unusual settings, morally problematic characters or, most frequently, striking social commentary.

Below are our seven favorite spies-turned-writers whose names are not necessarily associated with this curious profession.

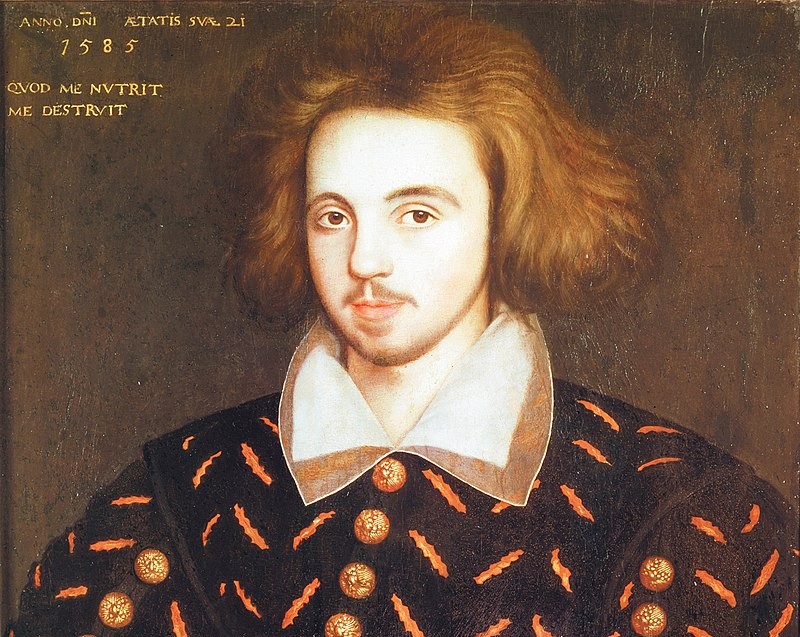

1. Christopher Marlowe (1564-1593)

When the facts about a writer´s life are scarce, history tends to offer creative interpretations of it. Such is the case with many Renaissance figures, including the intriguing Christopher Marlowe. The fact he was London´s most popular playwright at the time Shakespeare was just settling in the city and the unusual circumstances of his death still spark controversy.

Namely, he was born in the same year as Shakespeare and died at the age of 29 – exactly when the Bard’s career started skyrocketing.

This uncanny coincidence resulted in a range of theories about Shakespeare´s involvement in the event of Marlowe’s death. From the one suggesting he killed his famed opponent to pave his own way to glory, to the idea he later used Marlowe´s unfinished works to establish his name in the theatre world, the lack of facts inspired various creative assumptions.

What makes the whole story even more curious is the allegation Marlowe was a government spy. In fact, this seems to be the likeliest cause of his death, with various sources suggesting his killing was a government-sponsored association made to look like a tavern brawl. A piece of evidence emerged only in 2001, indicating that Marlowe got a hold of sensitive information that made him a possible threat to the monarchy.

Today, Marlowe is well remembered for his lavish and controversial lifestyle, with his works being studied alongside Shakespeare’s. While his plays are far from spy fiction, they are highly reflective of the political world he was involved with, one obsessed with power and overreaching ambition.

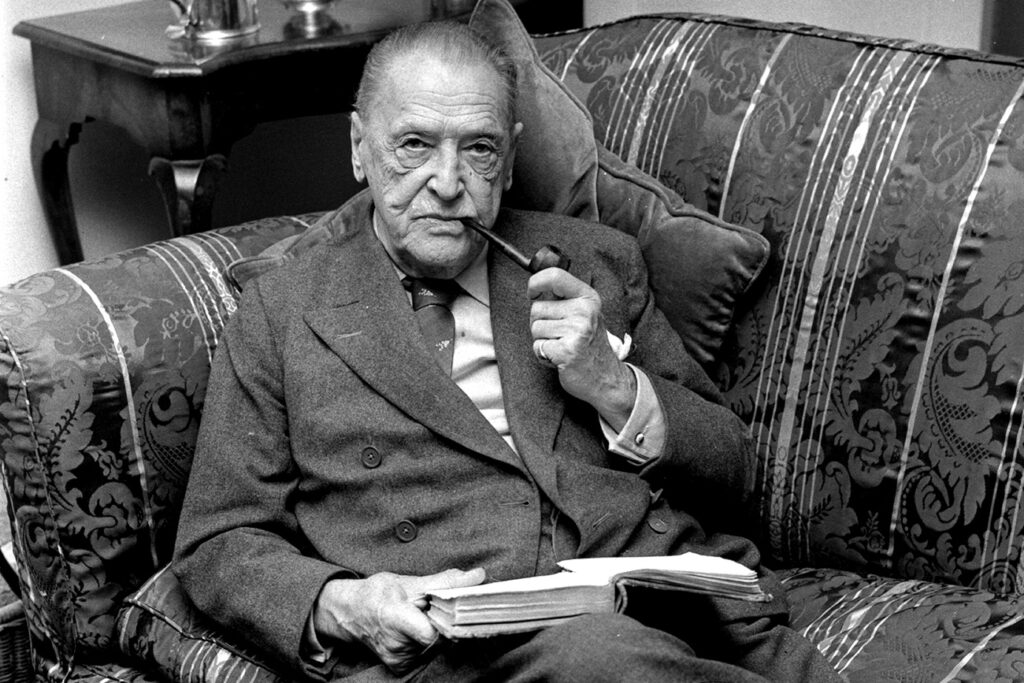

2. William Somerset Maugham (1874-1965)

By the time the Great War started, W. Somerset Maugham had already been an established literary figure. This very fact is what recommended him for the British intelligence service. His fluency in French and German came in handy for gathering information in foreign countries, while his primary occupation allowed for frequent travel without evoking suspicion. At the time he was recruited, he was living in Switzerland, where he was tasked with coordinating British agents and dispatching information back to the Kingdom (violating the Swiss neutrality laws along the way).

Maugham was soon sent to Samoa, the US, and eventually Russia, but was too late to influence the Revolution. After coming back home, he continued writing but was never allowed to publicly talk about his intelligence experiences according to Britain’s Official Secrets Act.

Sources suggest that much of his unpublished works had to be burned for this reason, but his 1928 collection of stories titled “Ashenden” is considered one of the founding works of spy fiction. Centering around a British agent in Russia, the stories are loosely connected to his own experiences but were so authentic that they inspired numerous spy fiction writers, including Ian Fleming itself.

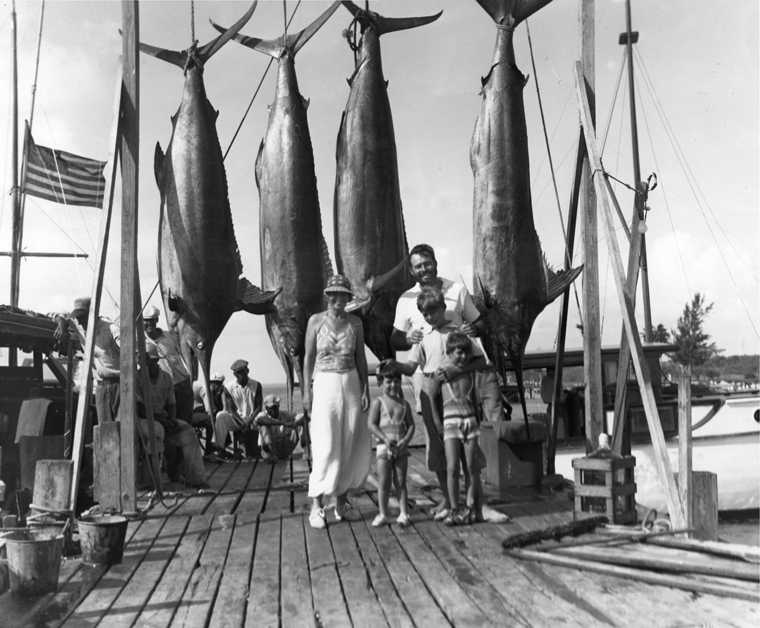

3. Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961)

Considering the adventurous life of Ernest Hemingway, it’s no surprise he managed to dabble in professional espionage alongside his literary work. Having travelled the world and developed a wide range of interests, the 1954 Nobel prize winner got into the habit of socializing with people from all walks of life —intelligence included.

For a long while historians couldn’t be conclusive regarding his possible involvement with the CIA, at least not until the Agency released a document revealing the nature of his espionage work.

“During World War II, Ernest Hemingway happily devoted much more of his time and energy to the field of intelligence than to his normal literary pursuits. He had relationships with the intelligence section of the US embassy in Havana as well as with at least three US intelligence agencies: the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI), the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). In addition, he dealt with the Soviet Union’s intelligence service at the time, the NKVD.”

After flirting with the US intelligence in the first couple of years of war, it seems Hemingway changed or was at least thinking of changing sides. In a book wittily titled Writer, Sailor, Soldier, Spy: Ernest Hemingway’s Secret Adventures 1936-1961, a former CIA operative and a historian at the CIA Museum explored the writer’s life in this period, presenting us with the possibility he was a KGB spy.

However, it was after the publication of Spies: The Riese and Fall of KGB in America that we got a more detailed account of Hemingway’s KGB affairs. Namely, it seems that he offered help to KGB agents on several occasions but was never recruited as he failed to deliver any politically relevant information.

In the context of Hemingway’s work, this episode may have had an influence in terms of character development and social commentary related to the war. And this topic remains one of the aspects that cemented his work for generations to read and discuss.

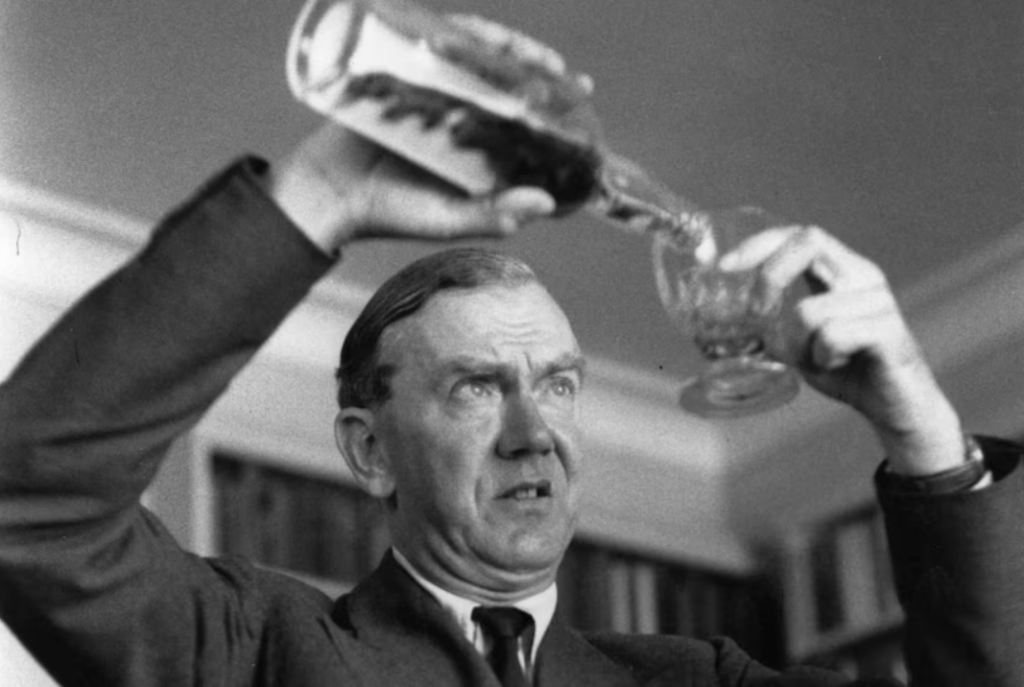

4. Graham Greene (1904-1991)

With his works directly addressing espionage and satirizing international politics, Graham Greene naturally fits into the community of former spies. In fact, this profession seemed almost second nature to him as several members of his family had already been involved with MI6. He was recruited for the service by his sister and was soon posted to Sierra Leone.

Here he had his first encounter with a major political scandal. Namely, his superior was found to be a communist spy, which later prevented Green from entering the US. The year was 1952 and the country was at the height of the Red Scare, banning or prosecuting people for much less than suspicious involvement with confirmed communists. The absurdity of this situation may have partly influenced his 1958 novel Our Man in Havana, which deals with the extreme steps both the US and Britain were taking at the time to fight the spread of communist ideas.

During the war, Green was actively working both as a writer and an intelligence officer, most likely because he enjoyed travelling to remote places. He resigned from the service in 1944, remaining fully dedicated to literature. He continued to use culturally diverse settings for his novels and to depict oppressive political ideologies, illustrating the banality of such affairs and often their futility.

5. Ian Fleming (1908-1964)

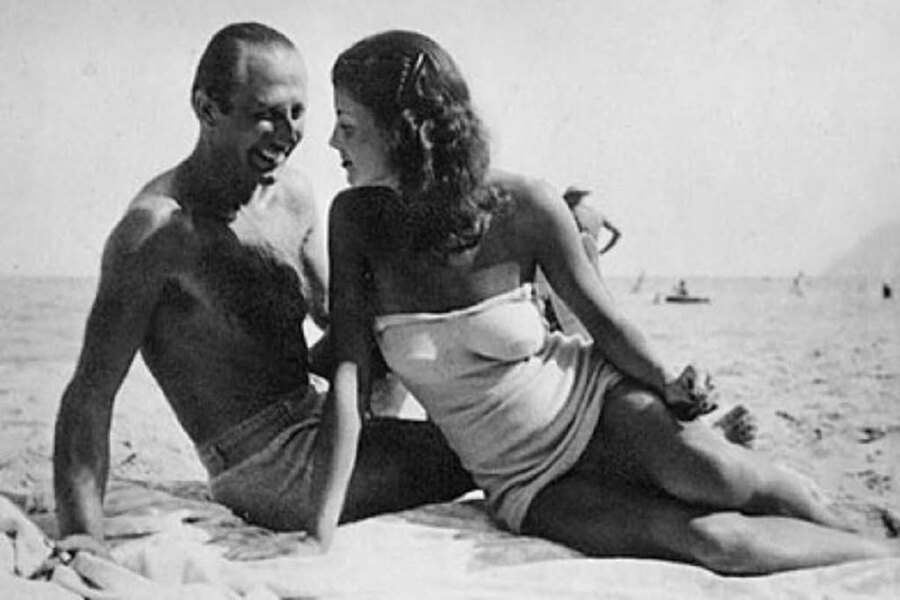

It is quite widely known that the creator of the famous secret agent 007 drew his inspiration from his own experiences as a Naval Intelligence officer during World War II. His code name was “17F,” and his line of duty encompassed a wide spectrum of espionage activities. Hence his masterful depiction of the spy world in his 39 James Bond novels, which remain chefs-d’oeuvre of the genre even today.

Bond himself was quite famously inspired by a real-life person named Dušan “Duško” Popov OBE. He was a Serbian lawyer and businessman who served as a double agent for MI6 during World War II.

One of the most legendary stories that connects the two together is the night at the Casino Estoril hotel in Portugal, where Popov is said to have gambled £50,000 of the British intelligence money. This may have made Fleming flinch with alarm, but it also seems to have left a lasting impression. So much so that the scene found its way into Casino Royale, becoming one of the most iconic moments in Bond lore.

6. Roald Dahl (1916-1990)

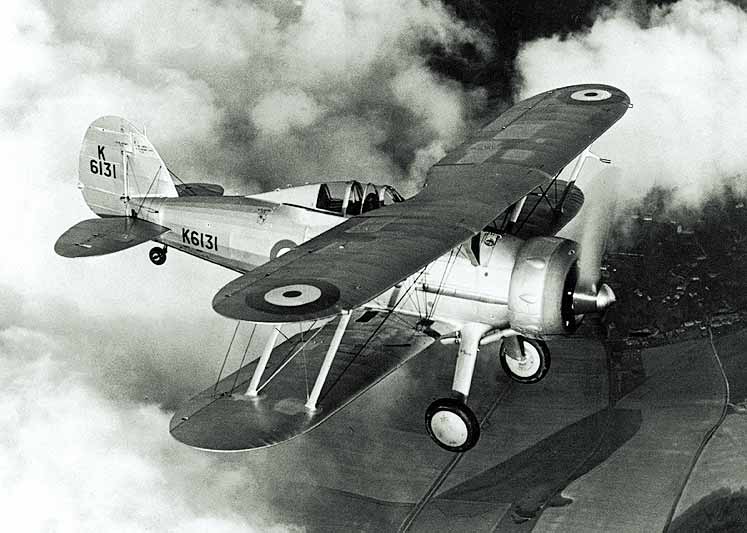

It was not until a nearly fatal plane crash that Roald Dahl was recruited to the British Intelligence Service. He was serving as an RAF pilot (after quitting a factory job in Tanzania) when he suffered an incident in Libya in 1941, which eventually led to his change of profession. He was recruited by the British Security Coordination (BSC), a part of MI6 established with a mission to spy on the US.

As part of his intelligence work, Dahl was expected to use his affability to gain trust and gather sensitive information, while also sharing pro-British propaganda. This work is well documented in his biography as he was active for years. His task was to make friends among the US political elite, which he did quite well considering that he was close with people like Eleanore Roosevelt and Harry Truman. He was also expected to handle press relations and use his war experience as a fighter pilot to bring America closer to the British war cause.

Dahl’s writing career started after meeting C.S. Forrester, who inspired him to write a story about his wartime experiences. The work got published in 1942 and that’s how Dahl’s literary career was set off. Next year he already pitched a story to Disney, but this effort never went through.

Dahl’s path from a versatile war and intelligence officer to a children’s writer is perhaps the most extraordinary on this list. Although his works cannot be said to have been directly influenced by his espionage activities, he drew on his experience when he was asked to adapt Ian Fleming’s You Only Live Twice into a screenplay for the 1967 James Bond movie.

7. Dame Stella Rimington (1935-2025)

Source: https://www.thebookseller.com/news/mi5-director-general-and-spy-novel-author-dame-stella-rimington-dies-aged-90

As the first ever female director of MI5, Dame Stella Rimington is said to have played a major role in modernizing and humanizing MI5. She was faced with a challenge of navigating the sexist culture of the organization, successfully driving a major cultural change that is widely celebrated today.

Various sources including the BBC credit her as being the role model for the character of M played by Dame Judy Dench in Bond movies.

Following her retirement in 1996, Rimington turned to writing and soon published a memoir offering insights into her intelligence experiences. She transitioned into fiction with a debut novel At Risk (2004), which introduced the character of Liz Carlyle, a female MI5 officer navigating the modern world of counterterrorism.

While many critics at first dismissed her writing as lacking in cleverness and sophistication, today many agree it offers a valuable perspective on the field of espionage. By providing a female perspective on the intelligence world and cherishing old-school storytelling style, she is now praised for her subtle commentary on the emotional dimension of intelligence work.

Featured Photo: Ian Fleming. Source: https://sofrep.com/news/ian-fleming-the-mysterious-creator-of-james-bond/

- Writing and Espionage: 7 Notable Literary Figures Who Were Also Spies - September 22, 2025

- On Embracing the Fantastic in Literature: Coleridge vs. Tolkien - March 23, 2025

- 7 Everyday English Words Coined by Coleridge - May 27, 2024