When Mario Vargas Llosa wrote about Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s gem One Hundred Years of Solitude, he pointed out that Macondo is a world itself, just like Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County, a sort of a spiritual area aiming to portray a dimension of humanity which is not visible at first glance. I mention this due to the fact that writers who have contributed greatly to Irish short stories share an important role with the abovementioned authors. They attempt to transform plain narration into a verbal object, which then reflects the world in its entirety focusing on both complexity and immensity. Furthermore, Irish writers have delved into the realm of darkness while doing so, thereby choosing very eerie settings for their stories. This dark element shows that the short story, as a format, is the last free art and a space to play with human isolation, and all those deep unspoken moments shared between people who are pretty much lonely all the way to their core. This intense awareness of human alienation is characteristic of contemporary Irish storytelling as well. The darkness serves to shed a light on a very important matter, that of Ireland still being a pretty gloomy place, a fact that has crept into the art published in the country and contemporary authors are finding ways to channel this pain and include it in the work they produce.

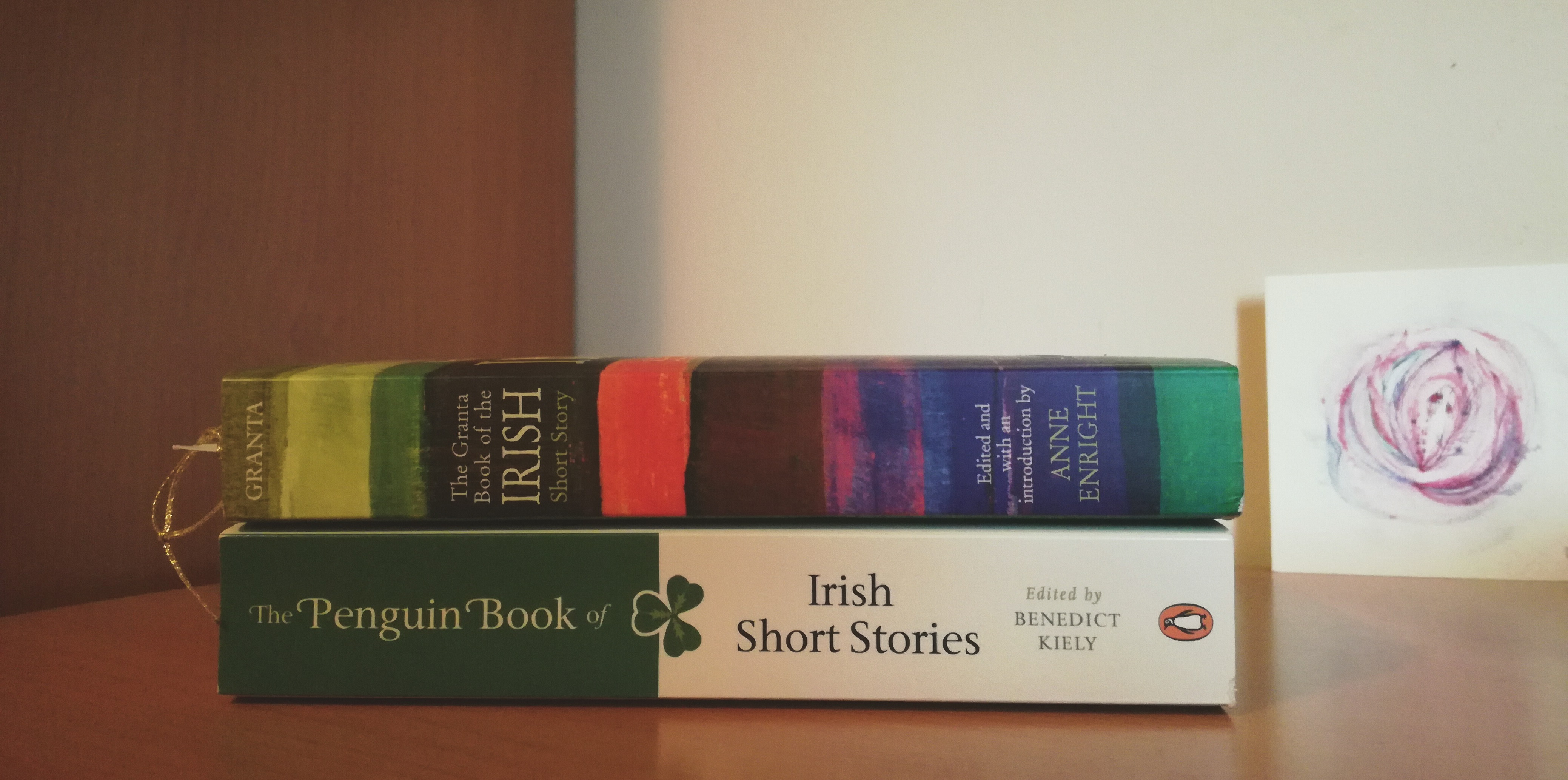

When discussing Irish writing, two important collections stand out. The Granta Book of the Irish Short Story, an anthology containing work produced in the twentieth century and edited by Anne Enright, who is herself a very important voice in Ireland’s literary production. The Penguin Book of Irish Stort Stories is yet another endeavour amounting to more than 500 pages of stunning prose writing, edited by Benedict Kiely. These collections are a great introduction into how both dark and vivid writing in Ireland truly is, and feature many authors that might have been marginalized in a certain way, but are truly significant for the development of the contemporary short story. To be more precise, dealing with a sense of place has a very big role in Irish writing, and it has been so for years. Just remember Joyce and his portrayal of Dublin, a place whose topography he managed to chart with acute precision. The element of being as authentic as possible is key to story writing meaning that one has to be specific and in no way general when approaching them.

Frank O’Connor, the eminent Irish short story writer, often voiced his opinion on storytelling pointing out that this form has flourished in those cultures and areas where the previous spoken forms have had to find a way of coming to terms with the ideology of modernization, which brings about new literary forms, as well as great change:

“The short story is born from the fragmentation of old certainties, and the absence of any new ones, and this produces in the writer a lyric response, ‘a retreat into the self in the face of an increasingly complex… reality.”

Another pillar of the twentieth century Irish writing, Seán Ó Faoláin, discussed another key element, that of writers embodying their writing, i.e. being some sort of priests who do not only write, but live their work. This somewhat romantic mood came to prominence when critics and authors considered Irish literature of the time as being part of the national resurgence to be a writer in Ireland. Furthermore, numerous short stories feature priests who share the loneliness of the common folk, as well as genuine sadness due to the folly of their congregation. The abovementioned Granta collection leaves them out, but it features two very interesting stories written by Maeve Brennan and Colm Tóibín dealing with female vision of loneliness, i.e. mothers who have to cope with their sons being away.

“Even the dust seemed to have found new places to settle, or to be settling in different places, and it seemed to her that in sweeping up dust, day in and day out, all she was doing was sweeping up the time since John had left – more dust every day, more time every day – and she began to think that all she would do for the rest of her life was sweep up the time since John left.”

– “An Attack of Hunger”, Maeve Brennan

By portraying a woman whose heart is in chaos, Brennan plays with dislocation in this story. Mrs Derdon cannot cope with daily activities and all she does all day long is utterly unimportant when compared to the absence she carries within. Whatever she does will not bring her boy back from service. Her cry for John resembles the words Betty Flanders directs into the void when attempting to come to terms with the emptiness surrounding her in Virginia Woolf’s novel Jacob’s Room:

“Don’t go with bad women, do be a good boy; wear your thick shirts; and come back, come back, come back to me.”

With the desired subject dislocated, women are left powerless, victims of the roles they are accustomed to, those of mothers and wives.

“But he wasn’t coming back, there was the realization of that stirring in her again, and it would start giving her orders again, taking charge, and she would obey it, getting up and sitting down and walking here and there and never easy anywhere, because the only ease that could come to her would come if she could just get down on the floor and put her face in the corner and let her mind wander away into sleep, but into a different, roomy kind of sleep, very deep and distant, where there was no worry.”

– “An Attack of Hunger”, Maeve Brennan

Problems featured in Irish stories include family, shame, humiliation and power (just to name a few). Writers have tried to deal with them in a realistic manner, which might sometimes come off as pessimistic or gloomy. However, what they have actually achieved is to use the short story as an area in which things are kept real, especially at their deepest, darkest level. Stories mirror what our lives truly consist of, they entail having to cope with the difficulties on a daily basis without an ultimate escape route.

“We know now. Now that there’s enough death to challenge being alive we’re facing it that, anyhow, we don’t live. We’re confronted by the impossibility of living – unless we can break through to something else.”

– “Summer Night”, Elizabeth Bowen

- Editor’s Picks: Celebrating Women in Translation Month - August 3, 2022

- Literary Travelogue: An Interview With Jelena Vukicevic (Visibaba) - May 23, 2022

- Special Feature: Review of ON BEING ILL (Uitgeverij HetMoet) - February 8, 2022